By Professor David E. Weber and Bruce Sallan

The Evolution of Technology series continues with a detour to a form of television that is largely extinct: The Television Movie. Also known as Movies-of-the-Week, they were once a staple of the major networks’ schedules back in the days before Fox, Cable, and even VCRs, let alone DVRs. It was also the focus of my first career for a quarter century. Look me up on IMDB or Wikipedia to learn of my sordid past in showbiz!

The highest-rated television movie of ALL-TIME – read more about it later on! It was an international sensation!

The highest-rated television movie of ALL-TIME – read more about it later on! It was an international sensation!

In fact, my very first published writing was about the sad direction that television movies took during a low period in the form when every sensationalized true-crime murder story was glorified into a TV movie. It was called Murders of the Week and I like to believe its words helped usher out that shameful period in an otherwise pretty noble and enriching entertainment form.

I’m going to lift some of the text from that article to detail the history of the television movie form. The TV movie provided me a wonderful opportunity to tell true and fictional stories, to travel literally all over the world, and to learn all the ins and outs of making movies, albeit on a limited budget but they were still movies in our eyes and we took great pride in our efforts.

Herewith, some of that history from my own article:

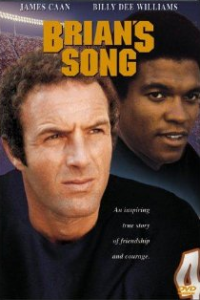

The official “Movie of the Week” began on ABC as a series of 90-minute movies in 1969. They were “entertainment” pieces, some pilots, and a couple of “special” movies ¬ bios, the animated movie “The Point,” etc. Soon, the “genre” movie began. These were ghost movies, vampire movies, women in jeopardy, and ultimately what became known as the “disease of the week” movie. “Brian’s Song” was probably the precedential movie of this form in 1970.

In the 70’s and early 80’s, the television movie evolved to what many consider the height of the form, where the subjects were often social issues that feature films were rarely touching. Gambling (“Winner Take All”-1975), homosexuality (“That Certain Summer”-1972), and rape (“A Case Of Rape”-1974) were a few of the subjects explored. Later, drunk driving (“M.A.D.D.: Mothers Against Drunk Drivers”-1983), lost and abducted children (“Adam”-1983) and incest (“Something About Amelia”-1984) were explored. The television movie was literally changing the consciousness of the American public about these fundamental issues. Drunk driving laws were clearly severely stiffened as a result, missing children on milk cartons became a sad but necessary by-product of “Adam”, and rape was definitely exposed for the heinous crime it is. Laws and protocols were being changed significantly.

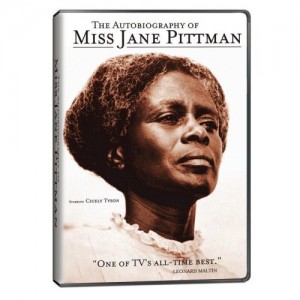

Mostly, these subjects were approached as a “social issue” and fictional stories were created. Experts in the area were utilized in the creation of the stories and the networks Broadcast Standards and Practices departments were scrupulous in demanding accuracy and the proper research of the facts. An extension of this “social issue” movie and probably one of the best television movies ever made was “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman”(1974). It was fiction, yet it clearly explored very socially relevant issues.

Real life true stories were also done, but more often they were biographies about “heroes” — major American figures like presidents such as FDR or Kennedy, or controversial stars like James Dean, or heroic athletes like Roy Campanella.

There were clearly an equal number of what were often called “programmers,” which were “high concept” women in jeopardy, genre, or log-line ideas. As often as not, they were the lesser quality of the form. But, they were original stories.

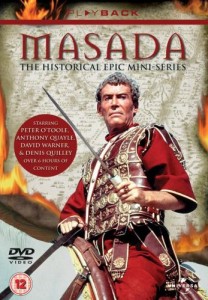

In the 70’s, the form was almost exclusively done in a 2¬hour format. Also, the mini-series evolved and became the blockbuster sensation of the form. These projects were usually based on “big” books or very “big” subjects. They were fictional as often as true. “QB VII”(1974) was one of the first. “Roots”(1977) was the epitome, garnering gigantic audiences, and utilizing the unprecedented scheduling plan of airing all the parts on consecutive nights. The “television movie” had now become a national event!

Artists heretofore alien to television flocked to the form as the ability both to explore interesting subject matter and/or to explore it in full length afforded opportunities not available elsewhere. “Sybil” (1976) gave Sally Field a role, which revitalized her career completely. Nick Nolte’s career was largely launched by his appearance in “Rich Man, Poor Man”(1976).

Who remembers watching television movies? Who remembers when all three networks had competing “Sunday Night Movies?” There was a seminal night in the seventies when CBS aired “Gone With the Wind,” as it did once each year in those days, NBC premiered on television, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” and ABC aired their “Elvis” TV-movie, starring Kurt Russell – all at the same time! “Elvis” won the night and television movies never looked back until…well, that’s another story.

With that, I’ll turn it over to Professor Weber.

I remember the Variety commentary Bruce wrote. Because I did not live in Los Angeles Bruce photocopied the column and folded up the paper photocopy, which he then placed in an envelope on which he wrote my address and glued a stamp. The U.S. Postal Service somehow got it into my hands several days later. But three decades ago, that was how you shared clippings with people you seldom encountered face-to-face—not even fax machines had yet become mainstream (When was the last time you used the noun “clipping” in a sentence?).

By the way, in Bruce’s portion of this “Evolution of Technology” article, he didn’t happen to mention that he won formal official recognition from the arts and entertainment community (an example is the Humanitas Award, considered prestigious in that industry) for specific contributions his TV movies made to society and culture. *

My memories of TV movies start with how effectively they often served a communitarian function. This is a fancy way of describing the “national event” concept mentioned by Bruce. A TV movie was often a cultural event around which many, perhaps a majority of, Americans came together in terms of shared attention and topic for dialogue. A moment in which scores of millions of us do more or less the same thing – watch a specific TV show – at more or less the same time, different time zones notwithstanding.

A TV movie was more compelling in this communitarian way than even a popular sitcom or hour-long drama series. A regularly scheduled TV show would be broadcast almost every week for about two to three dozen weeks from autumn to autumn. If you missed one episode, you could still “visit with” the characters the week before or the week after—and perhaps during summer reruns catch the episode you missed.

A TV movie, in contrast, would be shown once–or if extremely popular, perhaps rerun a second time that season. That one showing would fuel discussion in school, at work, at the kitchen table, for days.

If a TV movie was broadcast in the form of a miniseries – the communitarian function served by that TV movie played out across several weeks. I remember how in the mid-1970s, not too longer after I had finished college, I visited my parents at their house once a week for five or six weeks at a stretch to eat dinner and, at about 8.00 p.m., sit in the TV room to watch Rich Man, Poor Man (’76) and Roots (’77). Although as a typical twenty-something young man I effectively separated myself from my parents by earning living wages, setting up my own household and pursuing a social life outside my family circle, I enjoyed how TV movies turned out to enhance our family bonds.

Note by Bruce: Perhaps the single biggest day in the history of television movies was the broadcast of The Day After on November 20, 1983. I worked as the supervising executive at ABC when it was broadcast to the largest audience in the history of the form – over 100 million viewers!

What serves that communitarian function today? Many annual televised events, however enduring or still beloved, such as the Academy Awards, have lost audience numbers or percentages in recent years. Fewer of us may share the experience simultaneously. We can watch it a day later on Hulu, Youtube, a network website or, if we planned ahead, on DVR. An emerging or developing tragedy or cataclysm (e.g., the 9/11 attacks, the invasion of Iraq, the 2005 Asian tsunami, etc.) may rivet scores of millions of us as we watch the event happen in real time on television.

Many of us, though, follow the event on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media even as we watch its treatment on television. This reduces or complicates the communitarian aspects of the experience: You and I may sit in the same room watching The Weather Channel’s commercial-free coverage of Hurricane Sandy’s path of destruction. But how much sharing are we ultimately doing if I am toggling on my iPad between Fox News and MSNBC websites to track on their coverage while you are retweeting the on-the-scene observations made by your brother who lives on Staten Island?

Barbara Hershey won the Emmy for her performance in this TV Movie, produced by Bruce and it was also nominated for Best Movie of the Year by the TV Academy

Barbara Hershey won the Emmy for her performance in this TV Movie, produced by Bruce and it was also nominated for Best Movie of the Year by the TV Academy

The website IMDB.com tells me that the first full-length movie made for television was 1964’s See How They Run. I don’t remember it (I would have been 11 or 12 years old, indifferent toward fare I considered adult). During the next few years, though, I did watch two TV movies – Fame Is The Name of The Game (1966) and The Borgia Stick (1967) – that the networks promoted heavily. The marketing in print and on air called special attention to their design as movies made for television. I didn’t understand the concept of a movie made for television but for many years simply thought of a TV movie as a 90-minute-long episode of a one-episode TV show!

In college, I asked the professor of one of my film studies courses how he would describe the artistic differences between feature films and television movies. His dismissive answer: “Yes, the artistic difference is: a feature film is art, or can be; a television movie is ____,” and he used a word that rhymes with twit, which I think you’ll agree he was. I guess that the key differences would include: for television movies, keeping to a much shorter timeline (weeks** instead of months or years) for television movies in developing a script, completing principal photography and editing the footage; scripting and editing the television movie’s rising and falling action to accommodate commercial breaks; and less use in television movies of panoramic or long shots.

The television movie may be gone, but for many of us who enjoyed them, good memories remain. My favorite scene in a TV movie not produced by Bruce, or championed or green-lighted by him when he was a network executive, occurred near the end of Rich Man, Poor Man. Tom Jordache (played by Nick Nolte), abused by his father years before, eventually becomes a father himself. One day, Tom’s son happens to destroy the engine on Tom’s boat and, in panic, hides from Tom along the waterfront. Tom discovers what his son has done. Enraged – after all, the boat Tom’s meal ticket – Tom lurches around the waterfront looking for the boy. He finally winkles out the youngster, confronts him, spits out angry accusations. The camera shows Tom extend himself to full height, towering over the boy and raising his fists to strike him in punishment. Then we cut to a series of flashback images of Tom’s father unjustly and savagely beating him. Cut back to Tom and his son. Tom lowers his hands, relaxing. “Come on,” he says to his son, helping him up and draping a huge arm across his shoulders, “let’s teach you how to repair an engine.”

Cheesy? Maybe. But very touching. And, I would add, pretty good parenting.

*That’s very generous of the professor to inflate that award to include my whole body of work, but alas it was awarded for one television film, God Bless the Child, which at that time the first dramatic depiction of the plight of the homeless.

**The normal gestation for a TV movie was about 1-2 years, due to script development issues and other delays. The fastest TV movie ever made, to the best of my knowledge, was the last TV movie I produced. The day after Jesse Ventura was elected Governor of Minnesota, I pitched the idea to NBC. They said, “Yes,” if we could get it done and on the air quickly. We did. The Jesse Ventura Story aired NINE weeks later.

Get my new e-book on #Kindle for FREE and get the PDF version included – all FREE! Just click on the book cover image above! Offer expires Xmas Eve!

Get my new e-book on #Kindle for FREE and get the PDF version included – all FREE! Just click on the book cover image above! Offer expires Xmas Eve!