by Professor David E. Weber and Bruce Sallan

Our technology series continues a bit more on target by remembering the early days of home movies. We mean “movies” like in film, like in 16-mm, 8-mm and Super Eight, which were the primary sizes/forms when home movies were introduced. Professor Weber will lead off with his recollections and memories of this long-gone technology:

A projector casting flickering images onto a flimsy portable screen in a darkened living room: we called it watching home movies, once the only way an amateur filmmaker or chronicler of family life could work with the moving image.

In the 1920s, Kodak first marketed to consumers an equipment package consisting of a 16-mm camera, tripod and projector. The camera weighed seven pounds and “16 mm” (sixteen millimeter) referred to the width of the film one threaded onto a maze of sprockets inside the camera. Anyone with $335 (about five grand today) could now capture the motion in family events, picnics and everyday activities. No soundtracks — but synchronized sound reproduction didn’t even come to Hollywood until the late 1920s.

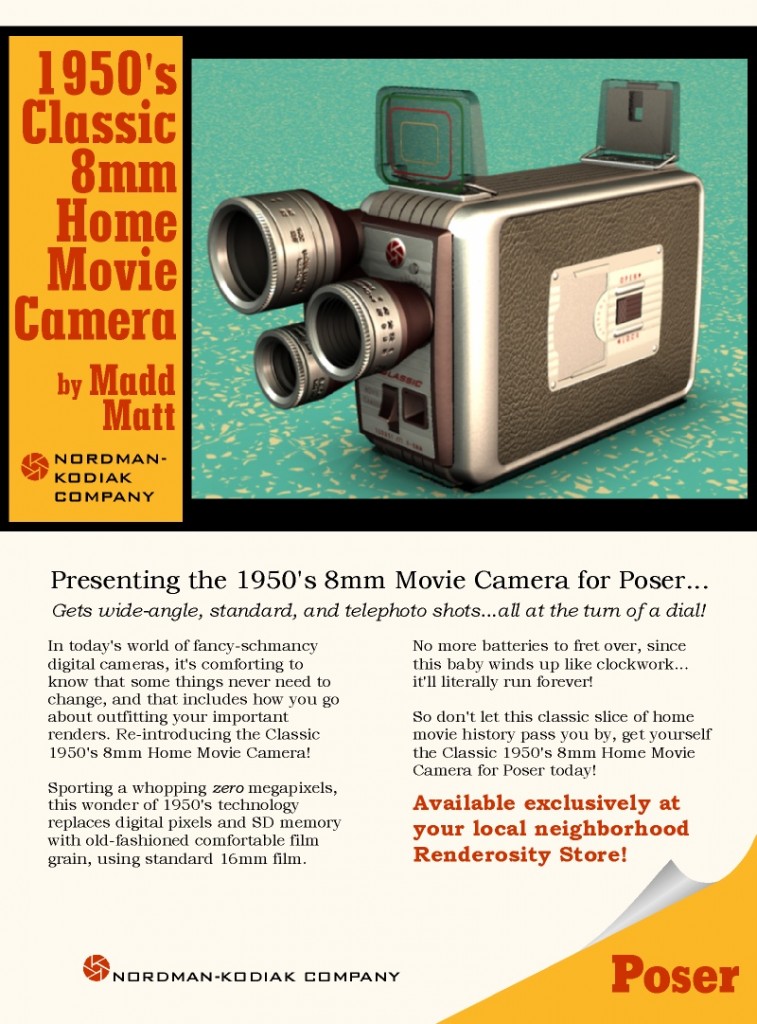

Manufacturers continued developing smaller, cheaper motion picture cameras for amateurs, and 8 mm film (narrower, lighter in weight) became standard. Elbow grease — not batteries or power cords — powered the early home movie cameras. Attached to and folded along its side, an 8-mm film camera would have a key, roughly the size of a credit card. You would snap the key outward and begin winding until the key turn no further, powering the camera for about 3-4 minutes, enough time to shoot 100 feet of film. Then reload, rewind and repeat, having tucked extra spools of film—each one packed a box about the size of a pack of playing cards—into pockets or a camera case.

During World War II, especially in the U.S.A. and Germany (countries manufacturing the most advanced mass-market movie cameras), a soldier’s wife or parent might present him an 8mm camera as a gift before he deployed. So much astonishing, horrifying or uplifting war footage from those cameras must have disappeared by now, although some of it does show up in documentaries. In 2010, a multi-episode cable TV documentary on the Nazi years in Germany procured visuals exclusively on amateur movies shot by German soldiers in combat and German civilians.

My dad owned a succession of 8-mm cameras, filming our family vacations primarily. Dad and I would drive to a certain local shop to drop off the exposed film one Saturday and return the next to retrieve our latest home movies. In a storage room, the owner, named Dale, would project Dad’s handiwork on a screen for us and commented approvingly (“Nice shot,” “Oh, that’s a great view of the mountains” and so on). Dad never bought a projector, for some reason, so I never saw our home movies except on those Saturdays at Dale’s establishment.

My Uncle Don also shot home movies. Because ambient lighting was dim and artificial lighting scarcely existed (except in bulky, expensive designs that generated garish, stark illumination) for amateur use, virtually all of what Don shot was outdoors — as were almost all the home movies I have mentioned thus far.

And Don owned a projector. From about 1959 to the late 1960s, our major family gatherings included watching Don’s latest home movies for about a half-hour after dinner. One Thanksgiving, Don’s oldest brother, Joe, passed the word that about fifteen minutes after Don’s show began, we should all follow Joe in walking out. The plan worked perfectly: Joe arose, exited the room ostentatiously and everyone followed suit, snickering. The heedless projector continued clicking as Don, suddenly alone in the room, brayed, “Hey, what the–?” as he lost his usually captive audience.

Obviously, systems for recording and playing images and sound on video have replaced home movies. Despite my nostalgia for home movies, I consider video recording and playback wonderful. Progressing from bulky VHS and Sony Beta systems of the late 1970s, to video functions in contemporary smart phones, video technology has in three or four decades become inexpensive and accessible to almost anyone. Several of my students hope to become filmmakers. They set up YouTube channels to go public with short documentaries and features. One evening in May 2012, in Paris, I used my point-and-shoot camera to record a 30-sec. video toast to my Uncle Don, just beginning hospice care in California. At 10.00 p.m. Paris time, back at my hotel, I uploaded the clip to YouTube, emailed the link to Don’s daughter (my cousin) at his bedside in California. Her iPhone alerted her to my incoming email and within 60 seconds Don could watch my friend and I toast him, on what was one of the last afternoons of his life. Could the Kodak product developers of the 1920s have imagined such versatile and poignant applications of the amateur moviemaking business they launched?

In about 2008, I came across a box full of old 8mm home movie spools. At a video studio in town, I had the home movies converted to DVD. The results: about 2 hours of old, silent images of several of our vacations, family activities and other events I had forgotten. To be honest, only about one-third of the material was watchable — my father was no Martin Scorsese — by being shot from too far back or too much shaky panning or glare from the sun. But for the first time in the more than forty years since Dale had first made it happen, I watched our home movies.

Wow, Professor, I loved your recollections. Mine are similar but with one large difference. My dad not only loved to take movies, but he loved to edit them and add titles.

He had a small editing machine – all-manual – in which, he’d view the film, cut and splice it with the built-in cutter and then tape the two piece together with special film tape. It was a cumbersome process but he was good at it. Given that the film reels were only 4 minutes of film, he’d combine several of them into a full-length 15-minute or so silent movie.

For titles, he had a felt board that had perforations in it onto which he could affix letters to form words and a title. Just writing this out makes the process sound so primitive compared to technology available today in taking, editing, and enhancing home video.

As David mentioned, this was all silent movies. Sound did not come to the home movie until the advent of videotape and video cameras. Those initial and very large, heavy video cameras are worthy of their own column.

A contemporary reflection for me occurred when I transferred most of the home videos I’d taken of my boys’ early years to DVDs. The boys had watched the home videos I’d taken over the years, but with the ease of having them on DVDs, they went through them with a fine toothcomb. My younger son found an adorable clip of his older brother, before my younger son was born. It was one of those embarrassing things that a sibling can use forever. And, it was priceless.

But, the thing I wondered most as they were watching these home movies, of which there were many and all were in color, in decent quality, and of course, with sound, was were they really remembering the moment or remembering the video of the moment?

I suppose it doesn’t really matter since it’s sort of like that eternal question of whether a falling tree makes a sound if no one is there to hear it?

Get my new e-book on #Kindle for FREE and get the PDF version included – all FREE! Just click on the book cover image below! Offer expires Xmas Eve!